Love it when unlikely sources celebrate unconventional urban youth ministries. I bought the May 2012 issue of Fast Company magazine because Steve Jobs was on the cover. I’m keeping it because of the 4,000+ word article celebrating the life and legacy of Father Gregory Boyle’s redemptive work with former Los Angeles gang members.

Love it when unlikely sources celebrate unconventional urban youth ministries. I bought the May 2012 issue of Fast Company magazine because Steve Jobs was on the cover. I’m keeping it because of the 4,000+ word article celebrating the life and legacy of Father Gregory Boyle’s redemptive work with former Los Angeles gang members.

(The cover story about the lessons Jobs learned during the “wilderness years” between his firing and return to Apple was worth the cover price. For example: “There was one other big lesson he learned from his Hollywood adventure: People remember stories more than products. ‘The technology we’ve been laboring on over the past 20 years becomes part of the sedimentary layer,’ he told me once. ‘But when Snow White was re-released , we were one of the 28 million families that went out and bought a copy of it. This was a film that is 60 years old, and my son was watching it and loving it. I don’t think anybody’s going to be beating on a Macintosh 60 years from now.'” But this blog post isn’t about wilderness lessons or even storytelling, per se. It’s about a phenomenal, if unconventional, youth worker and the transformational impact his ministry has on previously lost souls.)

Rather than summarize the article, I’m going to excerpt a bit here, and encourage you to read the rest.

When he arrived in Boyle Heights, back in the 1980s, Boyle began preaching at Dolores Mission, a little yellow church with a Spanish-tile roof and a hardy old tree by the door, a statue of Mary nestled where its two trunks diverge. At night, he would walk. No one knew what to make of this at first. The young men who lingered on the corners stayed aloof. Police stopped him outside a housing project, assuming he was there for drugs. But whenever guys would get beaten up or shot, he would visit them in the hospital. He had an ear for the neighborhood’s slang, and he adopted it as his own. And he was a Jesuit priest, in a neighborhood where gang members were mostly Latino. (“They’ll be running from the police, and they’ll still cross themselves when they pass a church,” Boyle jokes.) …

Eventually, some neighbors pooled their money and bought him a bicycle, so his walks, which seemed to have a calming effect, might cover more ground. After that, they would see the priest just about every night, pedaling through the projects.

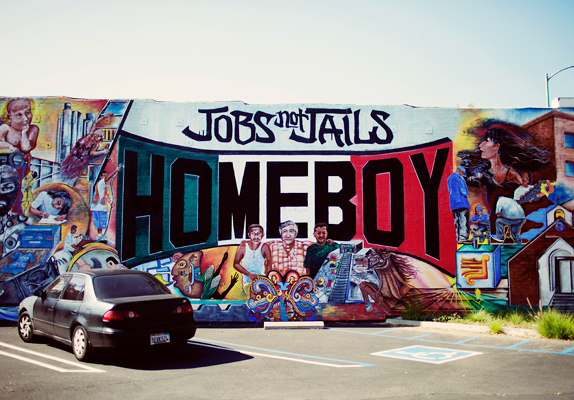

It occurred to Boyle during those rides that the biggest problem facing his community was the lack of work–especially for young men who had spent time in prison–and, by extension, a pervasive sense of hopelessness. So he started looking for jobs for the men. When he couldn’t find nearly enough, he decided to create some. In 1992, with a large donation from a movie producer, Boyle took over a small, shuttered bakery and founded Homeboy Industries.

By 2010, Homeboy was the country’s largest gang-intervention program, employing hundreds of felons–Boyle calls them his “homies”–at a cafe, a silk-screen shop, and other small businesses, and offering services such as free tattoo removal, GED classes, and counseling to thousands more. …

And:

Boyle had never planned to offer free tattoo removal. But when he kept failing to find a job for a young man with an especially unfortunate tattoo (f*** the world, on his forehead), he found a doctor who could erase it.

Homeboy’s businesses were born in much the same way. Boyle opened Homeboy Bakery because a bakery across the street had closed. “If it had been an upholstery shop, we would have opened Homeboy Upholstery,” he said. From Boyle’s perspective, Homeboy was primarily in the business of hiring people: “We don’t hire homies to bake bread. We bake bread to hire homies.”

And:

There was a theological point: “I always have a funny story at communion time that underscores that no one is perfect, and that communion is not for perfect people but for hungry people,” Boyle told me. But that probably matters less than this: The girls were rapt. After Mass, they came to him and lingered as long as they could. He spoke to each one in turn, as if she were his favorite niece: “You are so much more than the worst thing you’ve ever done.” He asked when they were getting out and gave them all his card, with his cell-phone number. “Come see me,” he said. “We have jobs.”

Back at Homeboy, young people kept arriving in Boyle’s office straight from prison, looking for work or money. “Have you eaten anything today?” Boyle asked a skinny, dull-eyed teenager. The boy shook his head. Boyle reached across the desk, slipping him a folded twenty in a handshake, and then squeezed his fist, instead of bumping it.

Boyle looked out into the lobby. “My God, where do all these people come from?” he said.There are 1.6 million people in U.S. prisons, and very few are in for life. The rest have to go somewhere, and do something. In California, 65% end up reincarcerated within three years, at an average annual cost of $46,700 per adult prisoner–and much more for Division of Juvenile Justice inmates. The recession has forced states to think about ways to reduce their prison rolls. In October, California began an 18-month process of cutting its state-prison population by 33,000, in part by transferring responsibility for some inmates to county authorities. Other states are watching closely.

Finally:

“You don’t know me,” the woman began. Her hair was pulled back into a thin braid that fell to the middle of her back. Her face was hard, opaque. “When my daughter was growing up, I was never able to put new clothes on her for school, not one time,” she said. Her voice started to shake a bit, but she kept going. Her daughter was grown now, with her own kids. The woman had started at Homeboy two weeks ago, as a janitor, and today, she got her first paycheck.

“I told my daughter I’m going to buy her kids an outfit for school,” she said. She tried to continue, but she started to cry, and then sob, her whole body shaking. “I wanted to thank you,” she said, struggling to speak. “I’m going to tell her how you helped me.”

“No,” Boyle said. “No, tell her you did it. You did it.”